Digital Ad Fraud – the Past, Present and Future

With both a nod and apologies to Stephen Hawking, the brilliant physicist and author of “A Brief History of Time”, I’d like to offer a brief history of digital ad fraud. I’ll also point out areas of ad fraud that are obvious but not currently often discussed, such as in the identity data used to target the media of ad campaigns. Finally, I’ll offer a view of what ad fraud may look like in the future such as the metaverse and in the blockchain enabled world of crypto and DeFi (decentralized finance). As an added bonus, if you make it to the end of this article I’ll fill you in on how my company’s name, Neutronian, is a nerdy reference to physics and an homage to Hawking in a way.

Digital ad fraud in the past

Long before Google went IPO in 2004, the original form of digital ad fraud was alive and well. Click fraud emerged almost the instant that the first few digital ads were served in the mid to late 1990s, and for the companies that first tested the paid search business model (Overture paid search and Yahoo, along with competitor search engines like Alta Vista) click fraud became an immediate issue. CPC (cost per click) was the first billing model for digital ads, especially in search, and fraudsters immediately took heed.

However, it wasn’t until Google went public that everyone realized the tremendous growth that the June 2003 release of AdSense (a self service search/text ads program where buyers signed up to purchase targeted search ads, and publishers signed themselves up to run such ads on their sites) had generated. From there, the idea of launching a website to generate clicks as path to riches became a hot topic (“hey let’s have a pizza party at the dorm and click on our site”), and the cat and mouse game of detecting and blocking incentivized clicks or click fraud was truly afoot.

The rest of the AdTech ecosystem took note. “If Google can grow this way by building a self-service exchange program for advertisers and publishers, why can’t we do that for the rest of the world?” — and with this, the programmatic exchange ecosystem was fully underway as everyone raced to follow Google’s explosive growth. Between 2007 – 2010, ad exchanges like Yahoo’s Right Media, Google AdEX, Microsoft AdECN, AdMeld, PubMatic, The Rubicon Project, and Open X all started to build RTB software that worked as a DSP, an SSP, an ad exchange, or some combination of the three.

Along with that growth in programmatic automation of advertising, additional forms of billing for ads continued to grow in popularity – beyond CPC, the forms of CPM (cost per thousand impressions, long the staple in traditional print publishing), CPA (cost per customer acquisition or sale), and CPL (cost per lead) took firm hold. And immediately, the digital ad fraud economy created groups and tools that allowed perpetrators to fake impressions, fake sales/acquisitions (for example using stolen credit cards), and fake leads.

However, just as the launch of AWS and their Elastic Compute (EC2) service in August 2006 allowed legitimate companies and websites to scale and grow much more rapidly than before (as no longer did one need to purchase a $100K computer to launch a business, just rent part of one), cloud computing and storage systems also paved the way for the growth of digital ad fraud at scale. Why? Prior to this time, ad fraud had been performed manually or via simple click programs, on a site by site basis that was growing on a linear basis. However, with the growth of cloud computing, the ability to create sites and automated click programs started to grow exponentially.

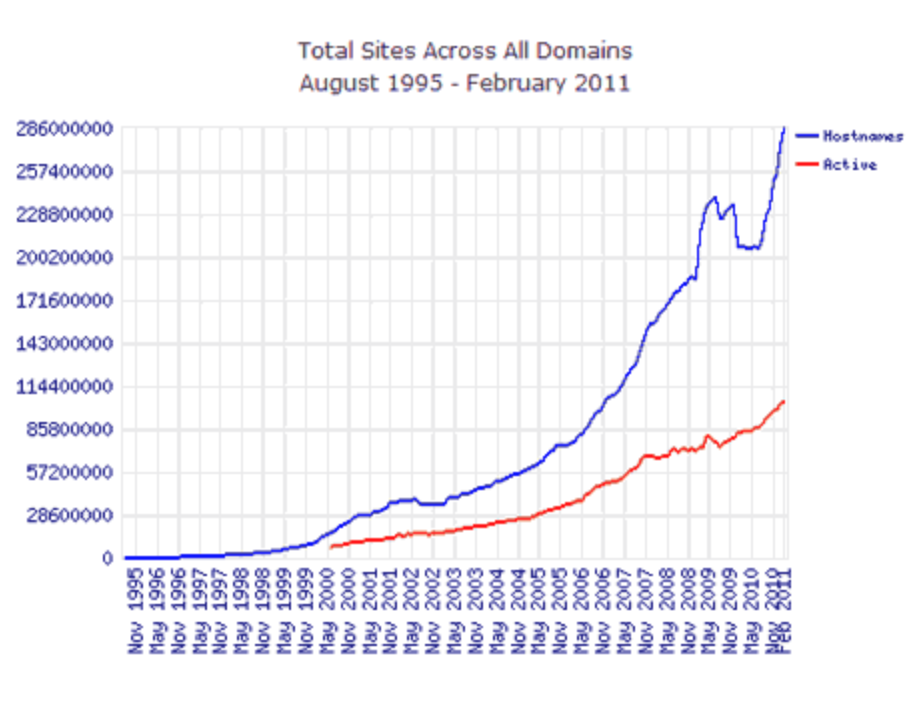

One researcher at webdevelopersnotes.com charted registered host names vs active sites during that time period, showing the extreme growth in domains (which could be used, for example, to spoof other and more legitimate domain names) and soon following a noticeably more rapid growth in sites:

To simplify things further, to execute on CPC click fraud one needs many sites and lots of clicks. For CPM impression fraud, ideally you’d want a massive amount of sites and a reasonable amount of clicks (both on ads and on pages of the sites, to mimic human behavior as closely as possible). For CPL lead fraud, you need to have automated software that can fill out forms on many sites. For CPA acquisition fraud, you need systems that can test stolen credit card numbers on a variety of sites as quickly as possible. All of this became vastly easier to do with the emergence of cloud computing and cloud storage.

This growth in sites and automation of fraud tactics quickly made the basic form of digital ad fraud prevention employed by advertisers and platforms – ie, having an internal team of staff manually check publisher sites and track campaigns via RFPs – obsolete. It also blew a hole in ad agency claims that their clients were protected from these forms of fraud, as it became very easy to provide screenshots of premium ad campaigns running next to unsafe content.

To defend against this new and evolving automation in digital ad fraud, a host of solutions began to appear around 2010. In order to protect against ads being served in formats that never had a chance of being seen (ie, in pop under windows or 1×1 pixels or simply at the bottom of a page where a user almost never scrolls), a group of tools called ‘viewability’ solutions appeared.

To prevent ads from being served into low-quality or non-existent content sites, or on porn or ‘not safe for work’ (NSFW) sites, brand safety tools launched that employed natural language processing (NLP) to evaluate the content and tone of a page.

And in 2012, to protect against the emergence of full networks of clickbot programs powered by thousands of computers each (also known as botnets), a suite of security solutions first known as NHT (non-human traffic) but now known as IVT (invalid traffic) detection emerged.

And per the previous dialogue on cloud computing as a tool for fraudsters, specifically for IVT, the growth in cloud data centers made it not just easier to execute bot fraud, but made it almost legal! Why? Because while IVT fraud had evolved from running simple click programs on single machines to using malware to infect and control thousands of machines – which is illegal, to install software on a device without a user’s permission – the growth in cheap cloud computing meant that fraudsters could program thousands of cloud servers to execute their click schemes for pennies, and programming a data center server to click on ads is not illegal at all. Which is why those fraudsters who have gone to jail for IVT schemes are doing so for wire fraud (collecting revenue under false auspices is clearly illegal) and not cybersecurity violations.

Thus was born the three core pillars of digital campaign verification that we have today in 2022 – viewability, brand safety, and IVT detection.

However, even with that, current estimates are that these known forms of digital ad fraud cost marketers billions of dollars each year. The game of cat and mouse will never end, as ad fraud is extremely lucrative and ever more innovative attacks are unleashed every year. So, just as with core cybersecurity of IT systems, marketers must have internal teams and vendors ever-vigilant to spot current and new threats in their cross platform campaigns.

Looking at the state of ad fraud today

Even with the background and knowledge that ad fraud is a serious issue and financial concern, large portions of the Marketing Tech ecosystem remain not fully protected, or not protected at all. For example, up until mid-2020, the common understanding was that Connected TV (CTV) ads were not susceptible to fraud “because it’s served in a walled garden type environment” was cringeworthy at best. With the massive growth in CTV it was a certainty that clever fraudsters would innovate to find ways to execute ad fraud schemes. Players like DoubleVerify and IAS began to speak openly of the issue, most likely because the CTV platforms themselves would not, with DV stating “Between January and April of 2020, DoubleVerify detected a 161% increase year-over-year in fraudulent CTV traffic”. Vendors began educating the market on CTV relevant fraud issues like server side ad insertion (SSAI). So CTV is an area of emerging understanding on ad fraud, but with such a rapidly growing market we can expect many more new forms of fraud to be discovered as well in this space.

However, when we look today at the world of data marketplaces such as those housed by LiveRamp, Oracle, or The Trade Desk, the implications of fraud in the data itself should also be considered. Marketers invest significant budget to better target the ads for their campaigns – after testing creative, placement, and channels, brands want to make sure that “25-45 year old soccer moms in the Midwest driving SUVs” will see their ads. But what isn’t known at all is what percentage of that audience data is real and what is completely fake or bot profiles, or what percentage of that data comes from tracking users on low quality or porn sites but then classifying them as high value consumers.

For example, the easiest way for a botnet operator to derive revenue from bot activity today would not necessarily be to run ads — it would be to create millions of fake audience profiles based on bot activity and load those IDs into the various data marketplaces for sale as ‘auto intenders’ or ‘iphone intenders’ because of their fake browsing activity. Given that less than 5% of data providers allow their data sources to be audited by an independent 3rd party audit firm, this represents a vulnerability in the ecosystem that surely is being exploited today by fraudsters.

It is well known that the market for 3rd party audience data is at least $12B per year in the US alone, and roughly $20B globally. Using conservative estimates, and proprietary data quality measurement techniques from both public sources and private ad campaign tests, the level of fraud in the audience data ecosystem likely exceeds 26.5%, or over $4B annually, in the US alone. Hopefully, this number will come down as brands become aware of the issue and embrace 3rd party auditing of data sources just as they do viewability, brand safety, and IVT detection.

Looking at the state of digital ad fraud in the near future

While it may seem that ad fraud can’t get any more ‘through the looking glass’ than it already is today, one only has to think of the metaverse and all of VR to realize that ad fraud will thrive there as well.

Imagine entering the metaverse and interacting with brands and players of all kinds, only to realize the vast majority of your engagement has been with bots. Far from being as easy to detect as a chat bot, the visual and auditory stimulation of the metaverse makes it harder than ever to detect real from fake. So, the most lucrative business of all time may end up being the one that creates the most lifelike “adult actress/actor” bots in the metaverse.

Or imagine that you’re a brand that has invested millions in prime metaverse real- estate, only to realize the vast majority of shoppers in your virtual store or the vast majority of attendees at your virtual conference are AI-driven. How will your chat bot service agents detect that they are also talking to chat bots, who may be using stolen credit cards to show enough activity to look real?

And we can go on from there, with pending developments in Web3/crypto/DeFi only adding to the potential exploits a fraudster may imagine. But yes, hopefully, also adding to the arsenal of tools that security providers will have to detect and mitigate fraud.

You’ve made it this far – so that geeky name, Neutronian

So what does Stephen Hawking have to do with inspiring the name Neutronian and our goal to fight digital ad fraud in its newest form of data fraud? Well, as my co-founder and I were looking for metaphors to explain the evolution of marketing campaigns and ad fraud, we joked that Newtonian classical physics could describe the early days of digital marketing – a few hundred or a few thousand or a few hundred thousand sites and ad categories that changed fairly slowly over time and somewhat predictably. But with the explosion of cloud computing and programmatic ad categories it became millions of ad categories and billions of sites, changing every second and many going out of existence rapidly after being launched, just as with quantum physics.

Once learning that the Neutron is the bridge particle between classical and quantum physics we asked ourselves “could we bring the measurement and stability of the early days to the current quantum explosion of data today?” And so we landed on Neutronian as a name.

Perhaps we might even compare Hawking’s search for a ‘Grand Unified Theory’ to our search to implement a comprehensive data quality framework in this very wild ecosystem. But that would not do justice to Hawking’s work, so let’s just say we give another very respectful nod to Hawking and those explorers like him as inspiration for our work. Plus, in any case the Neutronian.com domain was available, so that was the icing on the cake.